I didn’t set out to fix my focus. I set out to stop feeling mentally fried at the end of otherwise decent work days. The kind where you’re technically done, but your brain feels like it’s being pulled by five different conversations at once, most of them happening inside your browser.

What finally clicked was realizing that my operating system was no longer the primary means of switching contexts. There was a browser. Once I treated the browser as a workspace rather than a dumping ground for tabs, context switching quickly fell apart without adding tools, rules or discipline.

The context switch was happening within the browser.

Why apps were no longer the main issue.

For a long time, I assumed that context switching came from jumping between applications: a writing app, a browser, a chat tool, or a file manager. This used to be true. It’s not anymore.

Most of my work now lives in the browser. Written research, reference materials, documentation, CMS interfaces, communication tools, and analytics dashboards. Even when I thought I was “switching apps”, I was usually just switching tabs. The problem wasn’t how many tabs I had open. This was what these tabs represented.

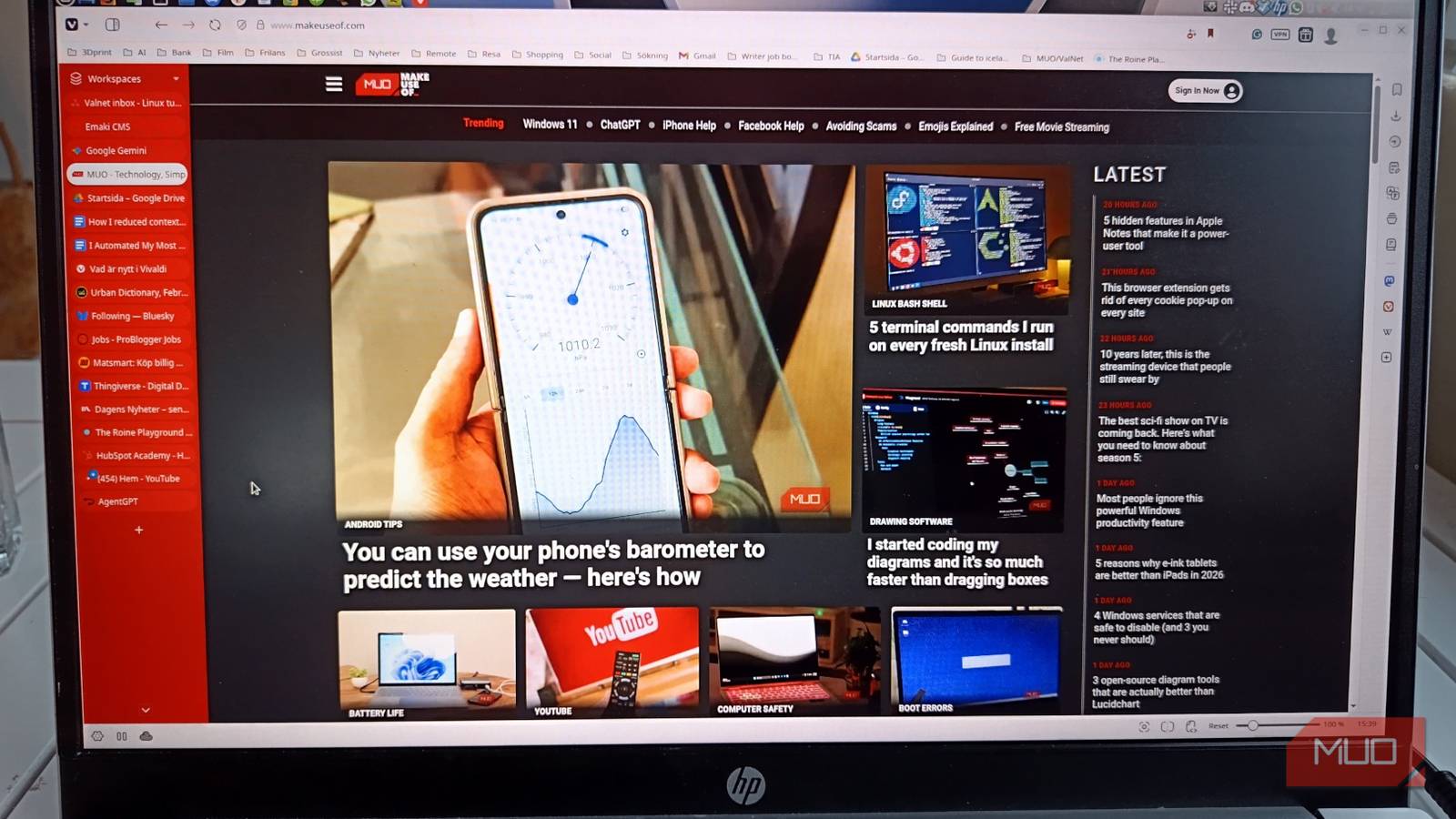

At any given moment, my Vivaldi tab bar contains a mix of deep work, background research, admin tasks, distractions, and things I’m afraid to close because I might need them later. This meant that every glance at the tab bar forced my brain to parse multiple contexts at once, even when I was trying to focus on just one task.

Once I saw this clearly, it became clear that reducing context switching meant changing how tabs were structured, not just closing more of them. I’ve found that Vivaldi is built for people who never close tabs, offering the exact tools needed to turn chaos into system.

I stopped treating my browser like a dumping ground.

Turning Vivaldi into an organized workspace

The first change was deciding that tabs should represent tasks, not time. Instead of letting the tabs accumulate in the order I opened them, I deliberately started grouping them using Vivaldi’s tab stack.

Each stack represented a single task or project. Writing, researching, or organizing. Each stack contains only tabs related to that task, nothing else. When I changed tasks, I changed piles. When a job was done, the entire stack could be turned off or parked without having to hunt through individual tabs.

Next, I introduced separate Vivaldi profiles. This was the single largest reduction in accidental context switching. Work lived in a profile. Personal browsing lived in the second. Admin and account heavy tasks resided in one third. The important part was not the number of profiles, but the principle that contexts do not mix.

This eliminated the subtle mental friction of looking at personal tabs while working, or trying to disconnect work tabs. As a long-term strategy, using profiles to organize tabs and sessions naturally reinforces segregation. The browser stopped being a place where everything happened together and started behaving like a set of rooms that you enter on purpose.

Changes that reduced mental switching the most.

Small Vivaldi features with big effects

Several small changes worked better than expected.

Vivaldi Workspaces allowed me to separate active work from suspended work. Ongoing projects reside in a workspace. Things I needed later but not today lived in the other. This meant that unfinished work could disappear from view without being closed or forgotten.

Tab tiling completely replaced window juggling for competing tasks. Instead of bouncing between tabs or dragging windows around the desktop, I tiled two or three tabs within a single browser window. It anchored my focus while still allowing for side reference.

Finally, I changed the way I thought about closing tabs. Because Vivaldi’s session handling is reliable, I quit keeping tabs open out of fear. I relied on session recovery in case I needed something later. This single decision dramatically reduced tab clutter and visual clutter.

Together, these changes meant less visible choices at any given moment. Less choice means less mental turnover, even when the workload remains the same.

Why did Linux redesign it?

Desktop behavior that leverages browser limitations

None of this would work if the operating system kept interfering.

On Linux, and especially with quieter desktop environments like Cinnamon, window behavior can be predictable. I pinned the browser to a specific workspace and adjusted the focus rules, so new windows didn’t steal focus. Notifications were trimmed to only those that required immediate action.

For those coming from other systems, Linux Mint’s Cinnamon desktop is often recommended as it provides a stable environment that doesn’t reset your habits. Since the system wasn’t constantly interrupting me, the structure I had built inside the browser remained intact. The tasks stayed where I put them. The context remains separate. When I changed tasks, it was because I chose to, not because something needed attention. This is where the browser redesign and the operating system reinforce each other.

Linux can be the best system for heavy content creation.

If you build it, you can build anything.

Why Redesign Beat Discipline?

What changed once context switching was accidentally stopped.

The most interesting thing was that none of it required much self-control. I didn’t get better at concentrating. I got better at environmental design.

By redesigning the way my browser represented work, context switching stopped being something I had to fight with. It just happened less often. When this happened, it was deliberate and easy to recover from.

At the end of the day, my browser no longer looked like a record of my every thought. It seemed like a set of completed and stopped tasks. Differences in mental fatigue became noticeable within days.

Why did it work when other reforms did not?

Changing context is not a personal failure. This is a design problem. Once I understood the browser as the primary environment where work happens, redesigning it became the obvious solution.

Vivaldi gave me compositional tools. Linux made this structure stable. The result wasn’t perfect focus, but something far more efficient: a workday that felt cohesive rather than fragmented.

And in the end that’s what made the difference.